David Cinque, Special Counsel – Kalus Kenny Intelex, Melbourne, Australia

Jessica Bell, Associate – Kalus Kenny Intelex, Melbourne, Australia

When it comes to trade mark protection and registrability, being a reputable market-leading brand is not enough to guarantee either the registration of a mark, or a successful opposition to the registration of a competing mark. Two recent decisions of the Australian Trade Marks Office (ATMO) highlight that the long-standing reputation of an established brand (and indeed a conceptually similar mark) is not enough for an opposition to succeed.

Further, relying too heavily on the shape and design of the underlying product itself in a mark can be fatal to an attempt to register that mark. Each of the Puma and Finish decisions, summarised below, illustrate these concepts respectively and the factors that the ATMO delegate is likely to consider when making its decision.

Puma SE v Sunday Red LLC [2025] ATMO 197

Puma SE (Puma), the global athletic apparel brand, opposed two trade mark applications filed by Sunday Red LLC (Sun Day Red). Sun Day Red is a golf and apparel brand founded by Tiger Woods in partnership with TaylorMade. Tiger Woods himself is the official face of the brand and he is heavily involved in its promotion and marketing.

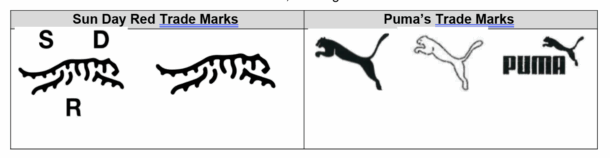

The case followed Sun Day Red’s application to register trade marks for its forward-moving tiger logos. Puma objected, arguing they were deceptively similar to its own famous bounding cat logo, which has been used in Australia on footwear, clothing and accessories since 1968.

The Sun Day Red trade marks sought registration under numerous classes, including Clothing (class 25), Sports Equipment (class 28), and Retail Store Services (class 35).

Puma argued that, while there were differences in the details such as the use of stripes, and the direction and angle in which the cat is moving, these details would not be noticed by an ordinary consumer with an imperfect recollection. It further argued that the Puma marks had acquired a sufficient reputation in Australia prior to the Sun Day Red priority date, and because of that reputation, any use of the Sun Day Red marks would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

Sun Day Red, in turn, argued that the only similarity is that the respective trade marks both involve depictions of wildcats and that the impression made by the Sun Day Red marks is an abstract representation of a tiger with distinctive open stripes.

The ATMO rejected both grounds of Puma’s opposition.

No Deceptive Similarity

The delegate emphasised that the relevant test does not just involve a side-by-side comparison of the respective marks. Rather, the delegate considered the overall impression made by the claimed marks in light of any recollection of the opponents mark which a person of ordinary intelligence and memory would have.

The delegate was satisfied that the stripes of the Sun Day Red trade marks are distinct and memorable features which create the clear impression of a tiger, distinct and separate to the overall impression of Puma’s logo as a different kind of wildcat.

The delegate also noted that the different positioning and orientation of the animals added to the overall distinction between the marks. Ultimately, it was found that even with imperfect recollection, consumers would still be able to tell the two apart.

No Likelihood of Deception or Confusion

While Puma’s Leaping Cat had acquired a reputation in Australia prior to Sun Day Red’s priority date, reputation alone is insufficient in order to succeed under this ground of opposition. There must also be a causal link between the established reputation and the subsequent likelihood of any use of the claimed mark resulting in deception or confusion. This likelihood is determined in light of various factors, including the strength of the opponent’s reputation and the degree of similarity between the respective trade marks.

The delegate found the differences between the respective wildcats were too notable and consumers would therefore be unlikely to assume any association or relationship between the two brands, namely, that consumers would not consider use of Sun Day Red’s tiger to be an extension of, variation to, or collaboration with Puma. This is particularly in light of the fact that Puma has not changed the basic shape of its logo in over 50 years.

Reckitt Benckiser Finish B.V. v Henkel AG & Co. KGaA [2025] ATMO 198

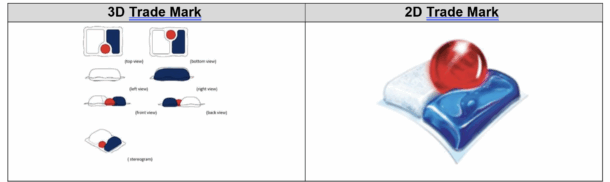

In May 2022 Reckitt Benckiser Finish (Finish) sought to register two trade marks in class 3 (automatic dishwashing tablets). One of these trade marks is an illustration of a three dimensional shape of a dishwashing tablet, and the other was a two-dimensional visual and colourised representation of that shape.

Henkel AG & Co. (Henkel), also a manufacturer of dishwashing tablets known as the Somat range, opposed the registration of both marks on the basis that it is not possible to distinguish Finish’s products from that of any competitor in respect of automatic dishwashing tablets.

Decision: Not Inherently Adapted to Distinguish

Ultimately the grounds of opposition were successfully established in relation to both marks and their registration was refused.

In their decision, the ATMO delegate explained that a trade mark’s inherent adaption to be distinguished must be assessed in light of the likelihood that other persons or traders would want to use the mark in connection with similar goods, and in doing so, would subsequently infringe the trade mark if it were granted. If a shape, in particular, possesses any ordinary significations, and other traders may want to use the shape for those ordinary significations, then a trade mark may successfully be opposed.

The delegate noted that a dishwashing gel capsule is likely to consist of a rectangular film on which are multiple set compartments which usually differ in bright and/or contrasting colours, and that, while shapes and colours of the capsule compartments can vary, these compartments all bear an equivalent functionality by shape as to their ability to fit efficiently in an automatic dishwashing machine’s receptable.

The three dimensional mark

The delegate found that the shape and configuration did not differ enough from what consumers would reasonably expect a standard dishwashing capsule to look like. As a result, the applied-for trade mark was considered to fall within the ordinary description of automatic dishwashing capsules. The delegate also noted that other traders would have a legitimate need to use the same or a closely similar shape.

The two dimensional mark

For similar reasons, the delegate found that the visual representation was not inherently adapted to distinguish. Other traders might legitimately wish to use signs closely resembling the mark for their ordinary descriptive meaning.

Key Takeaways

These two cases are a reminder that even where a brand has amassed a large reputation in the Australian market, this does not necessarily mean a trade mark opposition will fall in its favour.

The Puma case indicates that where the trade marks in question are sufficiently distinguishable, so as that there is not a real and tangible danger of deception or confusion, competitors may be able to adapt certain elements to their own branding – provided this is done in good faith, and that these elements are sufficiently adapted to be distinct in the overall impression made.

The Finish case indicates that dominance in a particular market does not give rise to exclusivity over shapes or signs that other traders or competitors may legitimately wish to use in respect of the same type of goods or services.