Find a firm

Search International Lawyers Network Members

Authors: Ronald Urbach of Davis+Gilbert and Robert Chappell Jr. of Davis+Gilbert

The Bottom Line

Advertisers and marketers who target NYC consumers should take note: the appointment of former FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection Director Sam Levine as Commissioner of the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP), combined with Mayor Mamdani’s recent executive orders on consumer protection, signals a major shift in enforcement priorities. With former FTC Chair Lina Khan serving as a key mayoral adviser, businesses can expect the kind of robust, aggressive oversight of advertising and marketing practices not seen since the Mark Green era. This alert outlines what advertisers need to know and how to prepare.

History of the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP)

The DCWP, formerly the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, was established in 1969 as the country’s first municipal consumer protection agency of its kind. Following the passage of the City’s consumer protection law, the department was created with broad authority to protect New Yorkers from deceptive business practices.

Under its broad authority, the DCWP oversees advertising that reaches NYC consumers — including national advertising. Along with the City’s Consumer Protection Law, the DCWP has undergone periods of heightened, aggressive enforcement against national advertisers believed to be non‑compliant with the City’s Administrative Code and the Rules of the City of New York. Further, in 1989, the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection set advertising guidelines for businesses requiring DCWP licenses. Examples of key areas of concern under the City’s advertising rules include pricing claims, offer terms, bait-and-switch tactics, free offers, and other false or misleading claims and illustrations.

New Leadership at the DCWP

Prior to the inauguration of Mayor Mamdani, it was announced that former Director of FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection Sam Levine would serve as the Commissioner of DCWP. During his time at the FTC, Levine oversaw enforcement, rulemaking, and policy work in many areas, including marketing, digital advertising, and consumer reporting.

While Levine served at the FTC, Lina Khan, co‑chair of Mayor Mamdani’s transition team, was the chair of the federal agency. Under the Khan‑era FTC and Levine’s leadership, the agency increased actions and rulemaking regarding issues concerning the advertising and marketing practices. Although Khan’s long-term role under the Mamdani administration remains unclear, Levine’s appointment signals a return to the DCWP’s aggressive oversight of business practices impacting New Yorkers — which includes national advertising and marketing practices.

The Mayor’s Recent Executive Orders

Mayor Mamdani’s two executive orders seeking to advance his affordability agenda, emphasizing pricing transparency, corporate accountability, and compliance with the City’s laws, are a recent indication of the administration’s intention to increase oversight and enforcement at the DCWP.

Strong Allies

At the signing of the two executive orders. Mayor Mamdani was joined by NY Attorney General Letitia James, City Council Speaker Julie Menin, and Commissioner of the DCWP, Sam Levine. We can expect that the NY City Council will ensure that the Mayor and Commissioner have sufficient resources to accomplish their consumer protection mission. Standing side by side, NY Attorney General James will support the consumer protection mission both by words and action.

Implications for National Advertisers and Marketers

While these executive orders concern junk fees and subscriptions, each largely mirrors initiatives of the Khan‑era FTC. The practical implications of such consumer protection monitoring and enforcement in New York City will likely play out for national advertisers and marketers. In the immediate term, with Mayor Mamdani in office and the appointment of Commissioner Levine, businesses should prepare for a potential return to robust, aggressive oversight by the DCWP of national advertising and marketing that reaches New Yorkers.

Drawing from the strong record of consumer protection at the FTC during Chair Khan and Bureau Director Levine’s tenure, we can look to that record for topics and issues to now be taken up by the newly revitalized NYC DCWP. Advertisers and agencies that take proactive steps now will be better positioned to avoid costly enforcement actions down the road.

Authors: Gary Kibel of Davis+Gilbert and Jeremy Merkel of Davis+Gilbert

The Bottom Line

The new year might mean the same to you, but for businesses, the turn of the calendar once again means a new set of privacy compliance obligations. 2026 brings new requirements in California, which has the most comprehensive regulatory framework and a stand-alone privacy regulatory agency, along with new state privacy laws in Kentucky, Indiana and Rhode Island taking effect.

CCPA Final Regulations

The California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) adopted a package of finalized regulations earlier this year, which take effect January 1, 2026. As discussed in our previous alert, businesses must be cognizant of critical areas that will require additional steps for compliance, including:

Additional CPPA Requirements

The CPPA has provided businesses with a list of additional items that businesses should know and prepare for, which includes, among other things, the following:

Display Opt-Out Request Status

A business must provide a means by which a consumer can confirm the status of their opt-out request, including those submitted through an opt-out preference signal, like the Global Privacy Control. For example, a business can display on its website “Opt-Out Request Honored” and indicate in the consumer’s privacy settings, via a toggle or radio button, that the consumer has opted out of the sale/sharing of their personal information.

Furthermore, businesses that sell or share personal information must process recognized opt out preference signals as valid requests to opt out for the device/browser and any associated profiles, and — where the consumer is known — apply the signal to the account and offline sales/sharing.

Requests to Know and Correct

For requests to know if businesses retain data beyond 12 months, consumers must be able to obtain all personal information collected on or after January 1, 2022, unless impossible or disproportionate, with individualized responses and secure delivery.

For corrections, businesses must now provide the consumer with the name of the source from which they received inaccurate information, or alternatively, inform the source themselves that the information is incorrect and must be corrected. Businesses must also ensure that corrected information remains corrected. For example, if the business regularly receives information from data brokers, it must make sure the corrected data is not overridden by inaccurate information later received from data brokers.

If a business denies a request to correct health information, consumers have the right to submit a 250-word written statement contesting the accuracy of health information, and upon the consumer’s request, the business must make that statement available to any person to whom it disclosed the contested personal information.

Expanding Right to Limit

The definition of “sensitive personal information” now explicitly includes personal information of consumers the business knows are under 16, as well as “neural data,” and confirms the sensitivity of several categories (e.g., precise geolocation, union membership, sexual orientation).

If a business is using consumers’ sensitive personal information for something other than the permitted uses set forth in section 7027(m) of the CCPA regulations, it must offer and honor consumers’ right to limit, and update privacy policies accordingly. Businesses may omit the “not inferring characteristics” condition only if they truly do not infer characteristics from sensitive data.

Enhanced Notices, Choice Architecture, and Universal Design Principles

All disclosures and interfaces for CCPA requests and consent must be easy to read, accessible, and free from dark patterns, with symmetry in choice and minimal steps to execute privacyprotective options. Notices must be conspicuous online and in mobile apps (e.g., in the app’s platform or download page), and accessible across modalities (including offline and device environments).

The regulations also codify specific requirements for the Notice at Collection, Notice of Right to OptOut of Sale/Sharing, Notice of Right to Limit, and the Alternative OptOut Link (“Your Privacy Choices” icon), including placement, content, and interactivity, with tailored offline and connecteddevice pathways.

Service Provider / Contractor Oversight

The regulations clarify that a business’s failure to conduct appropriate due diligence of its service providers — including ensuring that its subcontractor agreements comply with the CCPA and the regulations — will be factored into whether the business has reason to believe that a service provider or contractor is using personal information in violation of the CCPA and the regulations.

Metrics and Reporting for Large Data Handlers

Businesses handling 10 million or more consumers’ personal information annually must, by July 1st of each year, disclose metrics of volumes and median/mean response times for requests to delete, correct, know, optout of sale/sharing, limit, and, where applicable, access ADMT. Disclosures must state whether figures cover all individuals or only California consumers, with the business having the option of which metrics to disclose in its privacy policy.

Non-Discrimination Rules and Financial Incentives

The regulations reinforce that price or service differences tied to the exercise of CCPA rights are prohibited unless reasonably related to the value of the consumer’s data. Businesses must be able to substantiate valuations and provide a compliant Notice of Financial Incentive where applicable. In addition, nondiscrimination rights extend to the exercise of ADMT rights.

Insurance Clarification

Insurance companies that are “businesses” under the CCPA must comply with the regulation with respect to personal information that is not subject to the Insurance Code, such as website tracking for advertising or employment information (claimsrelated data governed by the Insurance Code remains outside the scope of the CCPA).

New State Privacy Laws – Kentucky, Indiana and Rhode Island

Three new consumer privacy laws take effect on January 1, 2026:

Among the patchwork of existing state privacy laws, Indiana and Kentucky’s laws are most similar to Virginia’s Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) and the Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA), as opposed to the more unique aspects of the CCPA. Covered businesses include those that:

Businesses who already comply with other state laws may not have to make significant changes to their privacy program. Businesses should, however, review their existing privacy policies to ensure they include the required disclosures under Indiana and Kentucky’s laws.

Rhode Island’s Unique Requirement

Rhode Island, notwithstanding its similarities to the existing laws, includes a unique provision that controllers must identify “all third parties to whom the controller has sold or may sell consumers’ personally identifiable information” (subject to an exception for disclosing trade secrets). Notably, the statute does not define “personally identifiable information,” instead referring to “personal data” (which is defined) in most of its provisions, so it is unclear how broadly this provision sweeps.

Controllers subject to Rhode Island’s law include those that:

This requirement has the potential to impose an onerous burden on companies that engage in a substantial volume of such sales.

What’s on the Horizon?

For the first time this decade, there are no consumer privacy laws signed by a governor waiting to take effect. But don’t get too comfortable. Legislation in Wisconsin, Michigan, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina is moving through committees. As always, it remains to be seen which of these bills will ultimately become law, but this is nonetheless a reminder that privacy law never sleeps.

Jessica Bell, Associate, Kalus Kenny Intelex, Melbourne, Australia

2026 begins with a number of changes to the Australian Trade Marks landscape, following the introduction of the Trade Marks Amendment (International Registrations, Hearings and Oppositions) Regulations 2025 (the IRHO Regulations).

The IRHO Regulations introduce a variety of procedural and technical updates to the Trade Mark Regulations 1995, including longer filing periods, partial replacement of protected international trade marks, and extended examination periods.

Divided into five comprehensive amendment schedules and two largely administrative schedules, the IRHO Regulations reflect recent changes to the Madrid Protocol administered by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). Below, we summarise the key details of Schedules 1-5 and outline what they mean for Australian trade mark applicants and holders. Schedules 6 and 7 are primarily technical, covering minor adjustments and the timing of when each amendment takes effect – Schedules 1 and 5 took effect on 19 December 2025, while the changes set out in Schedules 2-4 and 6-7 were effective from 19 November 2025.

Schedule 1 – Increased Filing Period for Notice of Intention to Defend

Schedule 1 increases the period for filing a Notice of Intention to Defend an Opposition (NID) to two months from the previous one month period.

This means that a party now has two months to file a NID in opposition proceedings relating to:

· the registration of a trade mark;

· an application to remove a registered trade mark for non-use;

· extensions of protection to an international registration designating Australia; and

· an application to cease protection of an international registration for non-use.

This additional time is particularly significant given the Registrar’s power to treat an opposition as successful where a defence is not filed on time. Commencing on 19 December 2025, the new filing period applies to any opposition where acceptance of the trade mark, non-use application, or international registration designating Australia was published on or after that date.

Schedule 2 – Partial Replacement of Protected International Trade Mark

Schedule 2 introduces the concept of a partial replacement of a protected international trade mark (PITM). This mechanism under the Madrid Protocol allows a trade mark holder to replace an earlier registration with a later international registration for some, but not all, of the goods or services protected by a trade mark.

Previously, Australia’s regulations only allowed for a full replacement of the goods or services protected by a trade mark. As a result of this change, a later international registration will no longer automatically replace an earlier Australian trade mark in its entirety where both are owned by the same entity and cover the same goods or services.

This change is beneficial to Australian trade mark owners because it provides greater flexibility to manage their portfolios, without risking the loss of any valuable existing rights. Instead of a trade mark owner being forced into an all-or-nothing replacement, they can now update their registrations gradually, retain protection for important legacy goods or services, and better align their Australian trade mark strategy with their international registrations.

Although the change in Schedule 2 commenced on 19 November 2024, partial replacement is now available for any eligible trade mark, including those registered and protected prior to that date.

Schedule 3 – New Ground for Rejecting an International Registration Designating Australia

Schedule 3 introduces a new ground for IP Australia to reject an international registration designating Australia (IRDA).

From 19 November 2024, an IRDA may now be rejected on the basis that its protection would result in an asset being made directly or indirectly available to, or for the benefit of, any person or entity to whom assets must not be made available under the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 or the Charter of the United Nations Act 1945.

This means that that Australia’s trade mark system is now expressly aligned with its international sanctions regime, preventing trade mark rights from being granted in circumstances that could breach financial and trade restrictions.

Schedule 4 – Registrar’s Power to Revoke Acceptance of an IRDA

In addition to Schedule 3, Schedule 4 clarifies that where a notice of intention to revoke acceptance is issued by the IP Australia, a previously accepted IRDA will not automatically proceed to protected status. Instead, the grant of protection is paused upon issue of the notice, rather than continuing at the end of the opposition period.

This gives the applicant additional time to address the Registrar’s concerns before a final decision is made to revoke acceptance. However, importantly, an IRDA will still become protected 18 months after notification to Australia unless the Registrar notifies the International Bureau otherwise within that period.

Schedule 5 – Extended Examination Period upon request for a hearing

Effective from 19 December 2025, Schedule 5 introduces a new ground for ‘deferred acceptance’ of a trade mark, particularly where an applicant or holder requests a hearing. In these circumstances, acceptance of the trade mark application will automatically be paused, preventing it from lapsing if the examination process is not resolved in time.

Importantly, applicants will no longer need to make a separate request for deferment. The pause will end upon the earlier of the Registrar deciding to accept or reject the application following a hearing or the applicant withdrawing their request to be heard.

This change is particularly significant for applicants who request a hearing close to the acceptance deadline, as it removes the need to apply for an extension of time.

Key Takeaways

Ultimately, the IRHO Regulations reflect a refinement of existing processes while ensuring continued alignment with international trade marks regulations. These amendments provide procedural flexibility in favour of trade mark holders and applicants, but also introduce requirements to be aware of, such as the expanded grounds upon which an IRDA can be rejected.

The new United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Director John A. Squires was sworn in on September 22, 2025 and wasted no time that week in expanding patent eligibility for AI related inventions. In particular, the new Director presided over the September 26 Appeals Review Panel (ARP) decision in Ex parte Desjardins, Appeal 2024-000567. In its decision, the ARP begins explicitly steering USPTO claim interpretation policy under 35 U.S.C. § 101 in a new direction that aims to reduce patent eligibility scrutiny and potentially minimize the now-classic hurdles associated with interpreting abstract ideas and practical implementations thereof under the established Alice/Mayo framework.

In Desjardins, the ARP interpreted a claimed machine learning training pipeline as a technological improvement. In its analysis, the ARP identified at least the claim term of training a machine learning model including a plurality of parameters on a second machine learning task to “adjust first values of the plurality of parameters to optimize the machine learning model on the second machine learning task while protecting performance of the machine learning model on [a] first machine learning task” as constituting a patent eligible improvement on how the machine learning model operates. In supporting this position, the ARP referred to the specification-declared advantages of the claimed subject matter in terms of lower storage capacity requirements, reduced system complexity, and effectively learning new tasks without losing knowledge on previous tasks.

Until recently, such broadly claimed processing operations exemplified by the steps of adjusting parameter values and protecting past performance recited in Ex parte Desjardins were commonly interpreted as applying generic computer parts to an abstract idea. The ARP acknowledges its plausible departure from the previous norm practiced by most examiners and appeal panels, noting in its analysis that “under the [original] panel’s reasoning, many AI innovations are potentially unpatentable, even if they are adequately described and nonobvious, because the panel essentially equated any machine learning with an unpatentable ‘algorithm’ and the remaining additional elements as ‘generic computer components,’ without adequate explanation.” According to the ARP, “Examiners and panels should not evaluate claims at such a high level of generality.”

As put by Director Squires in a subsequent statement before the Subcommittee on Intellectual Property Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate October 9, 2025, “patent eligibility is not an abstract debate” but “a matter of national security, of resilience, and of ensuring that America’s system of innovation remains robust enough to confront the challenges of the twenty‑first century.” Advocating for less restrictive interpretation under 35 U.S.C. § 101, Director Squires’ statement further explains that “[s]ection 101 should not be misused as a blunt instrument to exclude entire technological fields” as “patent law must remain expansive if it is to remain true to its statutory text, to its history, and to its constitutional purpose.” In the few months since the ARP’s decision in Ex parte Desjardins, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has been largely following Director Squires’ leadership, finding new acceptance for broadly drafted processing claims within the Alice/Mayo framework.

In this regard, the PTAB panel in Ex parte Mittal, Appeal 2025-002097 (November 24, 2025) reversed patent eligibility rejections of a claimed method of retraining a deployed machine learning model to detect and correct data-drift over time. In its analysis, the PTAB identified the claimed method steps of generating “a validation dataset from live model predictions generating a validation dataset comprising a plurality of data points” in view of user preferences, “ranking the plurality of data points of the validation dataset in view of the user preferences”, and “retraining the deployed machine learning model utilizing a new training dataset based upon the validation dataset and the ranked plurality of data points” as reciting an improvement in the functioning of a computer rather than broadly directing use of a computer and machine learning.

Similar to the ARP in rehearing Ex parte Desjardins, the PTAB noted corresponding specification-declared advantages in automatically correcting data-drift and accounting for different parameters affected by user preferences. Furthermore, the PTAB directly cites Ex parte Desjardins as precedential, noting that “claims reciting particular improvements in training a machine-learning model reflected an improvement to technology.” With this precedent, the PTAB determined that the claimed method of retraining a deployed machine learning model in Ex parte Mittal recites a technological improvement in machine learning with sufficient specificity that distinguishes it from claims in other cases that were deemed abstract for merely applying machine learning or data visualization without disclosing any technology-specific method.

In another case, the PTAB panel in Ex parte Brush, Appeal 2025-002376 (November 17, 2025) reversed patent eligibility rejections of a claimed machine‑learning system that converts heterogeneous electronic health record data into model‑ready feature catalogs and iteratively improves model performance. In its analysis, the PTAB determined the claimed steps of “generating a prediction by running a first predictive model, of the one or more predictive models, against the set of features hosted in the first feature catalog, wherein the predictive model is configured to make predictions based on the correlations within the normalized population data; [and] evaluating the accuracy of the prediction by comparing the prediction to historical data; altering the first predictive model based on the accuracy of the prediction” integrate any mental process or abstract idea into a practical application.

Similar to Ex parte Desjardins and Ex parte Mittal, the PTAB in Ex parte Brush noted corresponding specification-declared advantages of the claimed machine‑learning system in addressing data transfer bottlenecks between data warehousing and analysis, enabling correlations within normalized data to drive predictions, facilitating model verification and updates as warehoused data changes, and avoiding bespoke, one‑off pipelines by using feature catalogs compatible across multiple predictive models. Furthermore, the PTAB directly cited to Ex parte Desjardins, noting its precedential weight in establishing that a “claim is patent eligible [when] it ‘reflects… an improvement to how the machine learning model itself operates.’”

In another case, the PTAB panel in Ex parte Wang, Appeal 2025-001388 (October 29, 2025) reversed patent eligibility rejections of a claimed machine learning pipeline that aligns multisensor time‑series data and trains a model to predict mechanical quality‑assurance failures. In its analysis, the PTAB identified the claimed steps of “training the self-learning application by submitting the modified corpus to the self-learning application,” including “using training data to perform the training,” “teaching the self-learning application to make a prediction of a likely failure… in response to the self-learning application identifying adverse conditions,” and “gaining experience, by the self-learning application, that allows the self-learning application to infer a semantic meaning from behavior of the set of attributes,” as not practically being performed in the human mind.

Similar to these other PTAB cases discussed above, the PTAB in Ex parte Wang noted corresponding specification-declared advantages in improvements to operations of a machine learning model. In this regard, the subject specification provided that time-aligned streams representing the time-series data culled from sensors in a manner allows the inference and correlation of various conditions and states of each attribute at different times and makes them appropriate for use as training data in a machine learning operation. Here, the PTAB again directly cites Ex parte Desjardins noting that the claimed steps and corresponding specification-declared advantages are similar to the “improvement to how the machine learning model itself operates” that the Board concluded “integrated the judicial exception into a practical application” in Ex parte Desjardins.

Notably, Ex parte Desjardins has not rendered any and all machine learning claims patent eligible. For example, the PTAB in Ex parte Kuusela, Appeal 2025-001619 (November 24, 2025) affirmed patent eligibility rejections of a claimed method of radiology therapy planning that lacked any limitations directed toward modifying or developing a machine learning model. In this regard, the claim at issue merely recites a computer-implemented method including accessing patient information for a patient, accessing an integrated dose prediction model that integrates a plurality of predictive models, selecting one or more predictive models, processing said patient information, and outputting the radiation dose distribution, with no additional elements that affect the form or function of the integrated dose prediction model. Here, the PTAB again directly cites Ex parte Desjardins in noting that the claimed method merely applies a judicial exception using generic computer components and does not improve the functioning of the computer itself, and lacks any improvement to computer functionality or to how the machine learning model itself operates.

Taken as a whole Ex parte Mittal, Ex parte Brush, and Ex parte Wang strongly indicate the PTAB is clearly following the precedent established in Ex parte Desjardins, which embody Director Squires’ statement before the Subcommittee on Intellectual Property Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate calling for an expanded interpretation of patent eligible subject matter. More pointedly, claim limitations reciting retraining deployed models as in Ex parte Mittal, converting health record data into model‑ready feature catalogs as in Ex parte Brush, or structuring machine learning pipelines as in Ex parte Wang may well have found difficulty in establishing patent eligibility without new guidance from the Ex parte Desjardins decision. It should be noted that each of these cases includes the PTAB reading advantages from the patent specification, and understood that one strategic approach to better position AI inventions for eligibility is to clearly pair claimed machine learning structures to explicit nuanced advantages within the patent specification.

In this manner, the PTAB has started to set a pattern of decisions showing expanded avenues of patent eligibility for unique machine learning models that may require little more structure than the method of radiology therapy planning provided in Ex parte Kuusela. While this article focused directly on machine learning structures, other recent decisions by the PTAB following Ex parte Desjardins with subject matter outside the immediate scope of this article have applied similar reasoning to system processing claims. Examples of such claims include those employing concurrent processing in Ex parte Williams, Appeal 2025-001079 (October 30, 2025); employing an AI model to change data stream formats based on detected circumstances in Ex parte Goyal, Appeal 2025-001692 (November 24, 2025); and employing application search processing that uses tracked user interaction signals from a first application to estimate intent and to modify result ranking delivered by a second application in Ex parte Paris, Appeal 2025-001701.

Notably, this new policy shift at the PTAB is occurring entirely within the existing statutory and regulatory framework, without requiring Congressional amendment or rulemaking, including any action on the proposed Patent Eligibility Restoration Act of 2025. The Federal Courts have likewise not yet addressed these emerging eligibility approaches, and it remains to be seen whether the Courts will adopt the same interpretive posture. For now, the PTAB decisions following Ex parte Desjardins signal a meaningful recalibration of patent eligibility analysis at the USPTO that should materially influence drafting and prosecution strategy moving forward unless and until the Courts or Congress intervene.

Authors: Marie Lussier, Partner, and Elizabeth Varkovetski, Articling Student, Fogler, Rubinoff LLP

Today, roughly 60% of the average Canadian family’s diet consists of prepackaged and processed foods. These are often high in saturated fat, sugars, and sodium and Health Canada has flagged those ingredients as major contributors to obesity, heart disease, and diabetes.

To combat these health risks and empower Canadians to make informed choices, Health Canada published the Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Nutrition Symbols, Other Labelling Provisions, Vitamin D and Hydrogenated Fats or Oils) on July 20th, 2022. The transitionary period allotted for in the amendments ends on December 31, 2025 and, at that time, important changes to Canadian food labelling requirements will occur.

In fact, as of January 1, 2026, most prepackaged foods that are high in saturated fat, sugars or sodium will be required to display a front-of-package nutrition symbol (the “Symbol”).

What is needed now?

Manufacturers must now determine whether their products require the black-and-white Symbol and ensure that the Symbol displayed meets the new format requirements.

What will be required over time?

In most cases, the threshold for packaged foods is 15% of the daily value for each relevant nutrient in a serving size.

Despite this, the legislature has provided for some important exemptions, including:

1. Technical exemptions for foods such as those sold at farmers’ markets and raw, single-ingredient meats, poultry and fish, and certain products with very small packaging, such as single serving coffee creamers.

2. Health related exemptions for foods recognized as having health benefits, including whole or cut fruits and vegetables, 2% and whole milk, and eggs, or any combination of exempt “healthy foods”.

3. Practical exemptions for foods where the Symbol would be redundant, such as packages of sugar, honey, maple syrup, table and flavoured salt, butter and other fats and oils.

Additional exemptions include foods with special dietary uses such as meal replacement and nutritional supplements and infant formula and foods.

What will this look like come January 1?

Soon, many grocery items will feature the Symbol with a magnifying glass to “call out” products that are high in saturated fat, sugars, sodium, or any combination of these. It of course remains to be seen whether manufacturers implement the new Symbol in a timely and effective manner, whether it will affect how Canadians shop and eat and how penalties will be meted out for those traders who do not comply.

Commodore, What Can You Learn From Drifters?

By James P. Flynn, Epstein Becker Green

Trademark lawyers eventually learn a hard truth: brands often do not die; instead, they drift.

Sometimes they drift quietly into nostalgia. Sometimes they drift into the hands of the entrepreneurial and well-advised. Other times, they drift along unattended. Of course, sometimes, they drift straight into court.

Few issues in intellectual property law reveal the fault lines between legal formalism and cultural memory as sharply as disputes over legacy brands:

Brands that stand the test of time innovate to stay relevant and build upon the product imagery that first captured customers’ hearts. So-called legacy brands and their associated images include Timberland boots, the Burberry raincoat, Tiffany diamonds, and Levi’s jeans. Even Disney, whose fantasy characters remain central to the customer experience. Each consumer-facing brand expanded its appeal while staying true to its foundational equities. Conservative Burberry got sexy by putting its tartan pattern on bikinis. Tiffany signed Elsa Peretti to design more accessibly priced silver and gold jewelry that was still distinctively elegant. Traditional Disney acquired Pixar’s more modern storytelling. By definition, legacy brands can also survive a spate of bad management, bad economies, even bad luck — but not in perpetuity.

[BigThink, “How one key obsession can build and drive a legacy brand,” October 14, 2025]

When a name outlives its original commercial enterprise, questions inevitably arise: Who owns the identity? Who speaks for the brand? And how much does history matter when measured against trademark registries? It seems like legacy brands have a way of returning, sometimes as beloved revivals, sometimes as legal problems looking for a forum.

There are two disputes that offer a useful comparative lens on how different legal systems confront these questions. One is unfolding now in Europe over the Commodore name, the other was litigated for decades in the United States over the name for The Drifters. In this piece, we revisit Marshak v. Treadwell, in which the author played a role as trial and appellate counsel, in a matter dealing very directly with the notion of a legacy brand. See 23 Entertainment Law Reporter. 47-52 (July 2001). We place that matter alongside today’s COMMODORE name dispute unfolding in Italy. The result is not nostalgia, but instruction: a reminder that brand identity, once untethered from disciplined legal stewardship, will eventually be claimed by someone else—with paperwork.

The Commodore Dispute: Legacy Meets Registration

For those hoping that this would in some sense be a straight music piece, the author hates to disappoint you, but the Commodore dispute in Italy has nothing to do with Lionel Ritchie. That would probably have made it too easy for all of us. Instead, this COMMODORE brand related to computers and technology:

A bit of background for those who can’t remember hardcopy games, tapes, and ten-minute load times: Jack Tramiel founded Commodore in 1958 as a typewriter company that would ultimately become a major force during the 80s computing boom.

It would be 1982 before the Commodore 64 took flight in international markets, and the Guinness Book of World Records would recognize it as the best-selling home computer of all time.

The brand is synonymous with retro gaming….

[McNally, Commodore CIC takes legal action against Italian rival]

In many ways, that COMMODORE brand could thus be seen, at first glance, like a brick house: iconic, solid, structurally sound. “How can she lose with the stuff she use?,” or so the rhetorical question would go. Indeed, “what a winning hand,” one might say. Yet appearances, as trademark lawyers know, can be deceiving. Even a brick house will collapse if the registrational and ownership foundation is neglected.

In December 2025, Commodore International Corporation (“Commodore International” or “CIC”) commenced proceedings in the Italian courts and the European Intellectual Property Office challenging trademarks held by Commodore Industries S.r.l., an Italian entity founded in 2017 that successfully registered the COMMODORE name and related marks in Italy and the EU. Commodore International contends that those registrations conflict with rights traceable to the original Commodore business and should be invalidated to allow the marketing of “authentic licensed products” under the historic brand name. See Tom’s Hardware, “Commodore International challenges rival’s trademarks in escalating brand dispute” (2025). This matter has been described as part of an ongoing, “bitter battle over the ‘true’ representation of the original company.”

The Italian registrant, for its part, emphasizes that its marks were examined and granted by national and EU authorities, were not successfully opposed, and therefore enjoy the presumptive validity accorded to registered EU trademarks. See Tom’s Hardware, “Commodore International challenges rival’s trademarks in escalating brand dispute” (2025).

What is striking about the COMMODORE dispute is that it is not framed primarily as a classic likelihood-of-confusion case. Rather, it is a contest over identity stewardship: whether the emotional and historical gravity of the COMMODORE name can displace later-issued registrations obtained decades after the original company’s collapse. Commodore International appears adamant as to its obligation “to protect its legacy and preserve the community’s trust in the original Commodore name…We recognize and deeply value the passion and dedication of the Commodore community, who have kept the spirit of the brand alive for decades. Our goal is to protect that legacy and to foster a positive, creative environment for all who love Commodore—past, present, and future.” Commodore International even promises hat “[p]arties interested in creating officially licensed Commodore products and experiences will be able to begin the conversation with CIC in the coming weeks, when an official Licensing Pipeline tool launches at commodore.net.”

But the registration and bankruptcy background here is complex, detailed, and, ultimately, leaves Commodore International a bit at sea over trademark rights. After the original Commodore International went bankrupt in the 1990s, rights to its trademarks were sold, abandoned, or otherwise fragmented over decades. Multiple entities have claimed ownership at different times, which leads to:

This kind of fragmentation is very common with older brands whose original owners disappeared or whose IP lapsed without active enforcement. When more than one party uses the same historic brand: Consumers may get confused about which products are “official” vs. licensed vs. aftermarket; Products with the name might have widely varying quality, harming the perceived value of the brand overall. This is often what legacy brands fear most when unauthorized or low-quality goods carry their names. The current Commodore situation includes Italian-branded tablets, laptops, and games that many in the community view as unrelated to the classic computer legacy, which complicates efforts to “revive” the brand in a respectable way. As the song goes, “Sail on down the line / ‘Bout a half a mile or so / … Time after time I tried/ To hold on to what we got but/….I know it’s a shame/But I’m giving you back your name/…”

Under EU trademark law, that fractured history leaves Commodore International with a difficult argument to win absent provable bad faith, non-use, or invalidity at the time of filing by the Italian registrant. See EUIPO, Invalidity and Cancellation Proceedings Overview. Legacy alone, without current qualifying use or a successful attack on the registration process, rarely suffices. Indeed, from a European trademark perspective, this is uphill terrain. EU trademark law is unapologetically administrative. If one registers first, uses properly, and survives opposition, the law tends to reward diligence rather than nostalgia. Legacy may supply a compelling press narrative, but narrative is not a statutory ground for invalidation. See EUIPO, Invalidity and Cancellation Proceedings Overview. As the Italian registrant has noted, the company and its partners, “for over seven years now, have been legitimately using the brand in compliance with both current laws and market rules.”

In other words, Commodore International now finds itself arguing that history should trump the registry, a position that plays better in common memory than in continental regulation.

The Drifters Litigation: Identity Anchored in Continuity

The U.S. courts confronted a remarkably similar problem—albeit in a different doctrinal posture—in Marshak v. Treadwell, a long-running dispute over the name The Drifters, an American pop and R&B/soul vocal group with well known hits such as Under The Boardwalk, Up on the Roof, On Broadway, Save the Last Dance for Me, Vaya Con Dios, Saturday Night at The Movies, There Goes My Baby, and Please Stay. Though the group seemed to have three distinct “golden eras” in the early 1950s, the 1960s, and the early 1970s, now registered The DRIFTERS as a trademark during that whole period. The Drifters, in terms of membership, “were the least stable of the great vocal groups.” The consistency through that period was George Treadwell, who had purchased the name, from Clyde McPhatter in 1955, as any review of the shifting lineups in The Atlantic Years, 1953 to 1972, shows.

Larry Marshak obtained a federal trademark registration for THE DRIFTERS in the late 1970s and promoted performances under that name. He also initiated suit against a rival Drifters group operated by Faye Treadwell, widow of George Treadwell, the group’s long-time manager. Treadwell counterclaimed that Marshak’s registration had been procured by fraud because it failed to disclose the existence of longstanding rights tied to the original group’s commercial legacy, including ongoing royalty income from recordings. A jury found fraud, and the district court concluded that Marshak’s registration was void and that his use infringed Treadwell’s common-law trademark rights, rejecting, as Forbes noted, “Marshak[‘s] conten[tion] that the band’s trademark lapsed and was his for the taking when the original group stopped touring in 1976.” Marshak v. Treadwell, 58 F. Supp. 2d 551, 565–70, 582-84 (D.N.J. 1999). On appeal, the Third Circuit affirmed, emphasizing that trademark rights can persist where there is continuous commercial exploitation—here, through licensing and royalties—even if public performance activity ebbs and flows. Marshak v. Treadwell, 240 F.3d 184, 198–203 (3d Cir. 2001). Subsequent enforcement proceedings underscored how deeply courts may entrench control over a legacy brand once identity ownership is judicially resolved. See, e.g., post-judgment orders. Further, “the Truth in Music Advertising laws were legislated in 35 of the 50 US states from 2005 to 2020 to stop promoters such as Marshak from assembling new groups of musicians and marketing them as well-known groups such as the Drifters,” as one source noted.

The notion and idea of legacy being more than simply have the same performers is captured perhaps in a sports analogy used at the Marshak v. Treadwell trial:

[Treadwell’s Counsel] Every time you see an advertisement from Mr. Marshak’s group that implies he has a direct lineage, you should think about that [i.e., the direct line the Treadwell group had that Marshak’s didn’t].

Why…? Well I think it is like a baseball team. Mr. Marshak could have his own baseball team if he wants. That’s fine. But Mr. Marshak can’t today have a baseball team even with a bunch of free agents who used to play on the Yankees and call his team the “Yankees” and talk about the great heritage of Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig or anyone else. The only ones who can do that today and market that today, legitimately are today’s [1998] Yankees, Paul O’Neil, David Cone, and people like that.

Is David Cone Whitey Ford? No.

Is Paul O’Neil Lou Gehrig? No.

But there is a direct lineage.

In this case the direct lineage—and we still have Johnny Moore[, lead singer on classic recording of Under the Boardwalk]. The direct lineage is George and Fayrene Treadwell up to the present. We are going to show that Mr. Marshak has attempted to misuse the mark to create an association or to imply an association that he doesn’t have and never had.

[Trial Transcript, Openings 79-80, Marshak v. Treadwell]

In my opening I showed you some statements from Mr. Marshak’s lead singer, who talked about the music making a difference and who talked about that music as pure and simple. Now, in the opening I drew an analogy to a baseball team and said there has been a direct lineage…I want to remind you of that analogy because I think that analogy still works

[Trial Transcript, Closings 782-83, Marshak v. Treadwell]

The jury, trial court, and then Third Circuit bought that argument. The courts also noted that trademark abandonment is not proven by nostalgia fatigue. Where goodwill continues to be exploited, even quietly, the law will not declare the brand dead simply because someone else arrived with a cleaner registration file. Marshak, 240 F.3d at 198–203.

That holding mattered then. It matters now. And it remains one of the reasons revival-brand litigation in the U.S. is never as simple as “who filed first.”

Comparative Themes: Commodore and Marshak

Three important lessons emerge from the Drifters’ history in the Marshak litigation as applied to what is unfolding with Commodore.

1. Legacy Is Not Self-Executing

Both disputes demonstrate that historical resonance, standing alone, does not create enforceable rights. In Marshak, legacy mattered only because it was tethered to continuous commercial exploitation recognized by U.S. common law. Marshak, 240 F.3d at 198–99. In the Commodore matter, legacy collides with a European system that prioritizes registration and formal use over historical narrative. See EUIPO overview, supra.

2. Fragmentation Creates Opportunity and Risk

In both cases, decades of fragmented ownership and inconsistent stewardship created openings for later actors to claim formal rights. Because of that fragmentation:

The Drifters litigation shows how U.S. courts may unwind those claims if fraud or superior common-law rights are proven. Marshak, 58 F. Supp. 2d at 568–70. The Commodore dispute illustrates how, in Europe, fragmentation may instead reward the party that successfully navigates the registration system first.

The contrast between Commodore and Marshak is not merely factual; it is philosophical. Common-law rights, residual goodwill, royalty streams, and consumer association all matter. Fraud on the PTO remains the original sin under US law. See Marshak, 58 F. Supp. 2d at 568–70; see also Herb Reed Enterprises, LLC v. Florida Entm’t Mgmt.,736 F.3d 1239, 1248 (9th Cir. 2013) (continued record royalties meant “that the record supports the district court’s determination that HRE did not abandon ‘The Platters’ mark”); accord Robi v. Reed, 173 F.3d 736 (9th Cir. 1999)(“when Paul Robi left the group, he took no rights to the service mark with him. Rather, the mark remained with the original group. Paul Robi therefore had nothing to assign to Martha Robi.”); Bell v. Streetwise Records, 640 F. Supp. 575, 580 (D. Mass. 1986)(priority of trademark rights established “by bona fide usage… consistent with a ‘present plan of commercial exploitation.’”). EU trademark law remains skeptical of such historical storytelling. Registration, use, and procedural vigilance dominate. If legacy owners fail to protect the mark contemporaneously, later registrants are not presumed villains; they are presumed compliant.

Neither system is wrong. But each punishes a different kind of neglect.

3. Identity Versus Administration

Perhaps the sharpest contrast lies here. U.S. trademark law remains willing to privilege identity continuity, i.e. that persistence of goodwill in the minds of consumers, over administrative formalities. See also Robi, 173 F.3d at 739–41. EU law, by contrast, places heavier weight on the orderly administration of registered rights, even where the equities feel unsettled.

U.S. and EU Strategies for Legacy Brands

Trademark law has little patience for nostalgia untethered from use. As Marshak made clear, goodwill need not continuously perform on Broadway to survive; sometimes it lives quietly up on the roof, sustained by royalties and licensing long after the touring stops. The mistake is assuming that because the lights are dim, the house is empty. As Commodore is now discovering in Italy, a legacy brand may look like a brick house, but without disciplined legal stewardship, someone else will eventually move in—and start charging admission.

Legacy-brand disputes often arrive wrapped in the language of authenticity. Courts listen politely—and then ask for evidence. In Marshak, authenticity mattered only because it aligned with provable commercial continuity. In Commodore, authenticity will matter only if it can be translated into recognized grounds for invalidation under Italian or EU law. Romance alone will not void a registration.

So, what are the practical steps and warnings we can take from these matters:

1. Do Not Assume Nostalgia Equals Rights–In both jurisdictions, sentiment is not evidence. Legacy brand owners must document continuous qualifying use, licensing activity, or enforceable goodwill. Otherwise, they risk losing the race to registration. Put more starkly, legacy brands require governance, not reverence: If a brand matters, someone must tend it. Dormancy without strategy is not patience; it is surrender. Still, at least in the United States, legacy brands often survive on nothing more than this magic moment of memory (and recording revenue) just short of abandonment. Use that fleeting moment when goodwill still exists but legal control is may be slipping to solidify one’s position and stop the slide.

2. U.S.: Invest in Common-Law Proof Early–In the United States, evidence of royalties, licensing agreements, historical promotion, and consumer association can defeat abandonment and even void a registration for fraud. Marshak, 240 F.3d at 198–203. Practitioners should build that record long before litigation. Royalty streams, licensing agreements, controlled exploitation are not afterthoughts. They are survival tools. Marshak, 240 F.3d at 198–203. What mattered was not the spotlight, but what continued under the boardwalk, that somewhat hidden but undeniable and documented continuing commercial exploitation.

3. EU: Registration Strategy Is Paramount–In Europe, failure to register, or to oppose promptly, can be fatal. Legacy brand owners should prioritize defensive filings, monitoring, and timely invalidity actions grounded in bad faith or non-use rather than historical identity alone. In Europe, ownership is rarely decided solely on Broadway (or Piccadilly or the Piazza della Scala); it is decided backstage, in contracts and registries.”

4. Fragmentation Demands Governance–Legacy brands without clear ownership structures invite opportunistic claims. Whether in New Jersey or Milan, courts are less sympathetic when decades of inattention create uncertainty that third parties exploit.

5. Authenticity Is a Business Argument, and the Law Requires Proof: Courts may acknowledge authenticity rhetorically, but outcomes turn on statutory criteria: fraud, abandonment, use, and validity. The lesson of both Commodore and Marshak is that brand identity must be legally curated, not merely remembered. Nostalgia is a market force, not a legal doctrine. It sells products. It does not substitute for use, validity, or truthfulness at the trademark office.

So, looking at Marshak and Commodore, the settings differ. The doctrinal frameworks differ. The lesson, however, remains stubbornly the same.

Trademarks are territorial. Rights in Italy or EU might be distinct from rights in the U.S., UK, or Asia. This means a revived brand might be able to operate in one region but blocked in another due to local registrations. This complicates licensing, product rollouts, and global marketing. Older brands like Commodore are tied to nostalgic communities, but “community” sentiment can diverge from legal ownership. Fans often care about “authenticity” and “history” more than current trademark documentation. Disputes on such issues, where different groups claim legitimacy, can fracture such “communities” and harm brand revival efforts. Decisions made purely for legal defensibility (e.g., registering marks broadly) may not align with what such enthusiasts see as “true” to the brand.

Legacy brands rarely disappear all at once. They fade. They drift. They linger in the background, waiting for someone to decide whether the music is over—or merely quieter. The legal battles over Commodore trademarks in Italy highlight broader problems for legacy brands — fragmented ownership, overlapping registrations, costly litigation, consumer confusion, and divergent geographic rights. These issues make it difficult for any one party to revitalize a historic brand without navigating complex legal, commercial, and community hurdles.

The law will not decide that question based on sentiment. It will decide it based on who kept the lights on, who collected the royalties, and who bothered to lock the door. So, keep the magic going and don’t ever skip a beat, and, like the Drifters sang, …

Let the music play

Just a little longer

Just a little longer…

Make the music play

Keep this magic going

Keep those trumpets blowing …

Don’t ever skip a beat for

She may slip away…

By Kriton Metaxopoulos, Managing Partner, at A. & K. METAXOPOULOS AND PARTNERS LAW FIRM

Fairly recently, Greek Parliament passed a Bill introducing serious changes to the representation powers of Greek CMOs in an effort to strengthen their position in the Greek market. These changes seriously affect direct licensing in Greece and introduce rules that clearly favor Collective Management Organizations and limit the right of authors to individually exercise their rights.

More specifically:

Article 7Α: Collective licensing with an extended effect

1. In relation to uses of works or other subject – maters of protection, except from audiovisual works, within the Greek territory, collective management organisations and collective protection organisations may alternatively, by the means of a statement to the user, represent also rightholders who had not authorized them accordingly. The representation provided under this Article applies provided that the following conditions are cumulatively met: a) the organization which makes the statement, is, on the basis of its mandates, sufficiently representative of rightholders in the relevant type of works or other subject matter of protection in Greece, b) the interests of rightholders are ensured, as they are provided by the law, and in particular the equal treatment of all rightholders, among others in relation to the terms of the license and of their ability to authorize or not different collective management organizations either in whole or in part the management of their certain powers or of certain works or of subject – matters of protection, c) due to the nature of the intended uses of works or other subject – matters of protection, the obtaining of the license from rightholders on an individual basis is typically onerous and impractical, namely it could not cover all rightholders involved, d) the publicity measures provided under sections k), ka) and kb) of paragraph 1 of Article 28 are met.

2. In the case where more organisations meet the above conditions, the legal consequences of the statement provided under paragraph 1 occur when all organisations are making it jointly.

3. Rightholders who have not authorised the organisation granting the licenses under paragraph 1 may at any time exclude from the organisation’s representative power any of their works or other subject – matters of protection or their uses by the means of a written or electronical declaration to him in accordance with section ka) of paragraph 1 of Article 28. In this case, paragraph 2 of Article 12 applies mutatis mutandis.

4. Paragraphs 1 to 3 shall not apply to mandatory collective management.

5. In the case where a collective management organisation grants licenses in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2, rightholders who had not granted him with such an authorization, shall have equal treatment with those who had proceeded to such an authorization.

6. For the legal protection of the works and of the rightholders who are represented by the collective management organisation or by the collection protection organisation, paragraph 2 of Article shall be applicable (as added with Article 14 of the Law 4996/2022 (paragraphs 1 to 5 of Article 12 of the Directive (EU) 2019/790).

In other words, authors are by law deemed to be represented by the competent CMO even if they are not represented by it by virtue of a mandate or on the basis of a bilateral agreement with foreign CMO and are not as a result entitled to direct license their works unless they have personally complied with their obligation to oppose in writing to this mandatory representation. This abolishes the basic principle of direct licensing/right to prohibit or authorize the use of a work which is introduced by both the Berne Convention and the WIPO Treaties in favor of authors. The reason for saying this is that according to Art 7A the CMO is not only presumed to represent but instead actually represents, by virtue of the law, any author who has not authorized the CMO to this effect and it is on the author to cancel this mandatory representation by filing a declaration of opposition to the local CMO.

This provision practically means that at the moment the CMO makes a public declaration on its website that it has “activated” art. 7A for the above ex lege representation (extended copyright license) then the author is deprived practically from his right to direct license his works unless he files an opposition declaration at the site of the CMO. The legal effects of the declaration begin 3 months following the filing of the declaration.

Already both AUTODIA and EDEM/the CMOs of composers and lyrics’ writers (but not GEA which represents producers/singers/musicians) have published in their website that they apply art.7A in relation to the use of music by Radio and TV Stations and subscribers’ TV channels.

(https://www.autodia.gr/article/29/horhghsh-syllogikon-adeion-dieyrymenhs-ishyos, https://www.edemrights.gr/el/syllogikes-adeies-dieyrymenis-ischyos/

For many lawyers practicing outside the United States, intellectual property protection and risk are most often associated with patents, trademarks and copyrights. Trade secrets are frequently treated as the forgotten stepchild—associated with employment law and contracts rather than as an independent body of law. But since the passage of the Federal Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) in 2016, trade secret issues and disputes have steadily increased, and are now increasingly impacting both foreign companies doing business in the U.S. and domestic companies doing business abroad.

Patent litigation has declined over the past decade, while trade secret case filings have grown significantly. Court decisions and administrative remedies have left patents more vulnerable to invalidation under §§ 101 and 112, and much of the juice has been squeezed from the fruit of massive patent litigation campaigns by non-practicing entities, sometimes referred to as “patent trolls.” These developments, coupled with uncertainty about whether patents can effectively cover emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, have driven many companies and lawyers to increase their reliance on trade secret law.

The creation of a federal claim for trade secret misappropriation under the DTSA has reinforced this shift by introducing more predictability into a previously fragmented legal landscape. Within a year of its passage in 2016, trade secret case filings rose by 25%, and last year over 1,200 trade secret cases were filed in U.S. courts. The stakes are often high: juries have returned verdicts in the hundreds of millions and even billions of dollars—though some awards have been reduced or overturned on appeal. At the same time, patent cases now face greater procedural hurdles and damages seem to be shrinking, making trade secrets an increasingly important tool for protecting and enforcing critical intellectual property in the U.S. Many plaintiffs also prefer trade secret cases because there is often a bad-guy narrative that is more compelling to a jury than the relatively dry, technical issues of patent infringement and invalidity.

The U.S. Legal Framework and Reach

Trade secrets are protected under both federal and state law in the United States. Most states follow the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA), while the DTSA operates at the federal level. A single dispute may proceed under both regimes, which have overlapping but not identical provisions.

For example, some states such as California require the plaintiff to identify its trade secrets with particularity before it can take discovery from defendants, creating a hurdle where a plaintiff sees smoke, but cannot quite show a fire. Federal courts have wrestled with whether to adopt this requirement, with one Court of Appeals—the Ninth Circuit, which includes California—very recently deciding that the plaintiff-must-go-first requirement does not apply under the Federal DTSA. Quintara Biosciences, Inc. v. Rufeng Bitztehc, Inc., 149 F.4th 1081 (9th Cir. 2025). These differences require a trade secret practitioner to be familiar with both state and federal regimes.

The DTSA is particularly significant for foreign businesses as it applies extraterritorially where conduct abroad has an impact in the United States. Limited activity, such as presenting at U.S. trade shows, partnering with U.S. firms, or hiring former U.S.-based employees may be enough to support jurisdiction over a foreign corporation under the DTSA. The DTSA also allows extraordinary remedies such as ex parte seizure orders, and provides access to the intrusive discovery tools of U.S. litigation that do not exist in most foreign jurisdictions.

The case of Motorola Solutions, Inc. v. Hytera Communications Corp., 108 F.4th 458 (7th Cir. 2024) illustrates the reach of the DTSA. Although much of the alleged misappropriation by Hytera occurred abroad—including hiring away Motorola engineers and developing infringing products based on their knowledge—the court held that Hytera’s high-level use of the trade secrets in U.S. trade shows was sufficient to establish jurisdiction. The court also concluded that the scope of the DTSA does not limit damages to derive from U.S. revenues, and allowed Motorola to seek damages based on Hytera’s worldwide sales.

Clients should be proactively advised on this expansion of the reach of U.S. trade secret law.

Trade Secrets and Artificial Intelligence

While the big AI copyright infringement cases have garnered most of the headlines in the U.S. in recent months, behind the scenes, artificial intelligence has also become a focal point for trade secret law. Because of human inventorship, eligibility and description requirements, patent protection may be unavailable, and trade secret law may provide the best protection for key AI assets. Algorithms, data compilations and AI model architectures may qualify as trade secrets if they meet the legal definition, which requires both secrecy—“reasonable measures to keep such information secret”—and that the information derives independent value from its secrecy. But trade secret owners must describe these with sufficient particularity in any litigation, and so must be familiar with both substantive and procedural aspects of trade secret cases, such as the use of protective orders to prevent public disclosure of these trade secrets.

Relying on trade secrets to protect AI-related innovations also presents unique risks. Competitors may misappropriate secrets through scraping, model querying, or even “prompt injection” attacks that coax proprietary information from systems. The opacity of advanced AI—the so-called “black box” problem—further complicates proof of misappropriation. And unlike patents, trade secret law cannot protect against “honest” reverse engineering or independent development. Further, business collaborations involving AI provide unique challenges to preserving trade secret protection because of the potential loss of secrecy. For foreign companies operating in the U.S. or with U.S. businesses, structuring agreements and compliance policies with these risks in mind is crucial.

U.S. Litigation

Like most types of U.S. litigation, trade secret cases expose clients to the distinctive features of U.S. litigation, including unpredictable juries that may impose massive damage awards and extensive discovery. U.S. discovery includes depositions, interrogatories, and extensive e-discovery. For businesses accustomed to civil law systems with limited disclosure, this can be intrusive and burdensome. And combined with extensive motion practice and expert witness discovery, these procedures can drive litigation costs to reach millions of dollars, even before trial.

Some clients also fail to appreciate the implications of the presumption in the U.S. that litigation should be public. While protective orders may prevent a business’s most sensitive information from being part of the public record, this presumption substantially increases the risk that a client’s trade secrets may become public. For this reason, clients should consider dispute resolution provisions requiring private arbitration in contracts that implicate their trade secrets, but consider a carve-out to permit emergency relief when necessary to “stop the bleeding” when trade secrets are taken.

Strategies and Preventive Measures

Given these challenges and the changing legal landscape, education and preparation are critical. Non-U.S. lawyers should become familiar with U.S. risks and standards related to trade secret law. Employment contracts, nondisclosure agreements, licenses, and many other commercial contracts touching the U.S. should be drafted with this law in mind. Internally, companies should implement and document confidentiality protocols, restrict access to sensitive information, and conduct thorough exit interviews with employees, with an eye towards protecting trade secrets. These measures not only reduce the risk of misappropriation but also help establish that the company took “reasonable measures” to protect its secrets—an essential requirement in U.S. courts.

When the possibility of litigation does arise, engaging experienced U.S. co-counsel early is vital to avoiding litigation, if possible, pursuing litigation, if necessary, and navigating U.S. trade secret litigation once the die is cast.

Conclusion

U.S. trade secret law and litigation are expanding, along with the reach of the DTSA, as patent protection may be shrinking. By understanding the distinctive features and changing landscape of U.S. law and helping their clients tailor their strategies and procedures strategies accordingly, foreign practitioners can help clients minimize risks while maximizing the benefits of trade secret protection in one of the world’s most dynamic and high-stakes legal environments.

Authors

Steve Hanle https://www.stradlinglaw.com/professionals/steven-m-hanle.html

Jason Anderson https://www.stradlinglaw.com/professionals/jason-anderson.html

Ahmad Takouche https://www.stradlinglaw.com/professionals/ahmad-takouche.html

David Cinque, Special Counsel – Kalus Kenny Intelex, Melbourne, Australia

Jessica Bell, Associate – Kalus Kenny Intelex, Melbourne, Australia

When it comes to trade mark protection and registrability, being a reputable market-leading brand is not enough to guarantee either the registration of a mark, or a successful opposition to the registration of a competing mark. Two recent decisions of the Australian Trade Marks Office (ATMO) highlight that the long-standing reputation of an established brand (and indeed a conceptually similar mark) is not enough for an opposition to succeed.

Further, relying too heavily on the shape and design of the underlying product itself in a mark can be fatal to an attempt to register that mark. Each of the Puma and Finish decisions, summarised below, illustrate these concepts respectively and the factors that the ATMO delegate is likely to consider when making its decision.

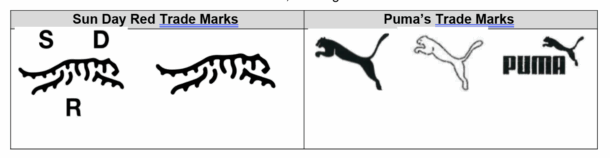

Puma SE v Sunday Red LLC [2025] ATMO 197

Puma SE (Puma), the global athletic apparel brand, opposed two trade mark applications filed by Sunday Red LLC (Sun Day Red). Sun Day Red is a golf and apparel brand founded by Tiger Woods in partnership with TaylorMade. Tiger Woods himself is the official face of the brand and he is heavily involved in its promotion and marketing.

The case followed Sun Day Red’s application to register trade marks for its forward-moving tiger logos. Puma objected, arguing they were deceptively similar to its own famous bounding cat logo, which has been used in Australia on footwear, clothing and accessories since 1968.

The Sun Day Red trade marks sought registration under numerous classes, including Clothing (class 25), Sports Equipment (class 28), and Retail Store Services (class 35).

Puma argued that, while there were differences in the details such as the use of stripes, and the direction and angle in which the cat is moving, these details would not be noticed by an ordinary consumer with an imperfect recollection. It further argued that the Puma marks had acquired a sufficient reputation in Australia prior to the Sun Day Red priority date, and because of that reputation, any use of the Sun Day Red marks would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

Sun Day Red, in turn, argued that the only similarity is that the respective trade marks both involve depictions of wildcats and that the impression made by the Sun Day Red marks is an abstract representation of a tiger with distinctive open stripes.

The ATMO rejected both grounds of Puma’s opposition.

No Deceptive Similarity

The delegate emphasised that the relevant test does not just involve a side-by-side comparison of the respective marks. Rather, the delegate considered the overall impression made by the claimed marks in light of any recollection of the opponents mark which a person of ordinary intelligence and memory would have.

The delegate was satisfied that the stripes of the Sun Day Red trade marks are distinct and memorable features which create the clear impression of a tiger, distinct and separate to the overall impression of Puma’s logo as a different kind of wildcat.

The delegate also noted that the different positioning and orientation of the animals added to the overall distinction between the marks. Ultimately, it was found that even with imperfect recollection, consumers would still be able to tell the two apart.

No Likelihood of Deception or Confusion

While Puma’s Leaping Cat had acquired a reputation in Australia prior to Sun Day Red’s priority date, reputation alone is insufficient in order to succeed under this ground of opposition. There must also be a causal link between the established reputation and the subsequent likelihood of any use of the claimed mark resulting in deception or confusion. This likelihood is determined in light of various factors, including the strength of the opponent’s reputation and the degree of similarity between the respective trade marks.

The delegate found the differences between the respective wildcats were too notable and consumers would therefore be unlikely to assume any association or relationship between the two brands, namely, that consumers would not consider use of Sun Day Red’s tiger to be an extension of, variation to, or collaboration with Puma. This is particularly in light of the fact that Puma has not changed the basic shape of its logo in over 50 years.

Reckitt Benckiser Finish B.V. v Henkel AG & Co. KGaA [2025] ATMO 198

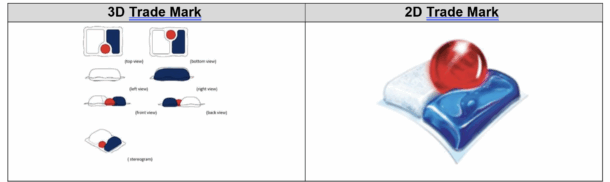

In May 2022 Reckitt Benckiser Finish (Finish) sought to register two trade marks in class 3 (automatic dishwashing tablets). One of these trade marks is an illustration of a three dimensional shape of a dishwashing tablet, and the other was a two-dimensional visual and colourised representation of that shape.

Henkel AG & Co. (Henkel), also a manufacturer of dishwashing tablets known as the Somat range, opposed the registration of both marks on the basis that it is not possible to distinguish Finish’s products from that of any competitor in respect of automatic dishwashing tablets.

Decision: Not Inherently Adapted to Distinguish

Ultimately the grounds of opposition were successfully established in relation to both marks and their registration was refused.

In their decision, the ATMO delegate explained that a trade mark’s inherent adaption to be distinguished must be assessed in light of the likelihood that other persons or traders would want to use the mark in connection with similar goods, and in doing so, would subsequently infringe the trade mark if it were granted. If a shape, in particular, possesses any ordinary significations, and other traders may want to use the shape for those ordinary significations, then a trade mark may successfully be opposed.

The delegate noted that a dishwashing gel capsule is likely to consist of a rectangular film on which are multiple set compartments which usually differ in bright and/or contrasting colours, and that, while shapes and colours of the capsule compartments can vary, these compartments all bear an equivalent functionality by shape as to their ability to fit efficiently in an automatic dishwashing machine’s receptable.

The three dimensional mark

The delegate found that the shape and configuration did not differ enough from what consumers would reasonably expect a standard dishwashing capsule to look like. As a result, the applied-for trade mark was considered to fall within the ordinary description of automatic dishwashing capsules. The delegate also noted that other traders would have a legitimate need to use the same or a closely similar shape.

The two dimensional mark

For similar reasons, the delegate found that the visual representation was not inherently adapted to distinguish. Other traders might legitimately wish to use signs closely resembling the mark for their ordinary descriptive meaning.

Key Takeaways

These two cases are a reminder that even where a brand has amassed a large reputation in the Australian market, this does not necessarily mean a trade mark opposition will fall in its favour.

The Puma case indicates that where the trade marks in question are sufficiently distinguishable, so as that there is not a real and tangible danger of deception or confusion, competitors may be able to adapt certain elements to their own branding – provided this is done in good faith, and that these elements are sufficiently adapted to be distinct in the overall impression made.

The Finish case indicates that dominance in a particular market does not give rise to exclusivity over shapes or signs that other traders or competitors may legitimately wish to use in respect of the same type of goods or services.

By: Daniel H. Bliss

Suppose you have filed a trademark application to register a trademark that identifies a source of goods/services for your business. During examination of the trademark application, the United States Patent and Trademark Office initially refused registration because of an alleged likelihood of confusion with a registered mark. What are the DuPont factors, and can you argue them in an attempt to overcome the refusal? If you do argue some of the DuPont factors must you address the same scope of similarity for these factors in a likelihood of confusion analysis? The answer is YES.

In re du Pont de Nemours & Co. established the following factors for consideration to determine whether there is a likelihood of confusion:

1. The similarity or dissimilarity of the marks in their entireties as to appearance, sound, connotation and commercial impression.

2. The similarity or dissimilarity and nature of the goods or services as described in an application or registration or in connection with which a prior mark is in use.

3. The similarity or dissimilarity of established, likely-to-continue trade channels.

4. The conditions under which and buyers to whom sales are made, i.e., “impulse” versus careful, sophisticated purchasing.

5. The fame of the prior mark (sales, advertising, length of use).